Community

TL;DR: I took a quantization challenge designed for CUDA experts, solved it in Mojo with AI assistance, and ended up 1.07x to 1.84x faster than the state-of-the-art C++/CUDA implementation. If you've ever wanted to write GPU code but bounced off the inherent complexity, this is your sign to try Mojo.

Why This Matters

Traditional GPU programming has a steep learning curve. The performance gains are massive, but the path to get there (CUDA, PTX, memory hierarchies, occupancy tuning) stops most developers before they start. Mojo aims to flatten that curve: Python-like syntax, systems-level performance, no interop gymnastics, and the same performance gains.

I wanted to test that with a real benchmark. So I took Unsloth's NF4 dequantization puzzle, a practical workload with a published baseline, and tried to beat it using only Mojo.

Here's what happened.

The Challenge: NF4 Dequantization

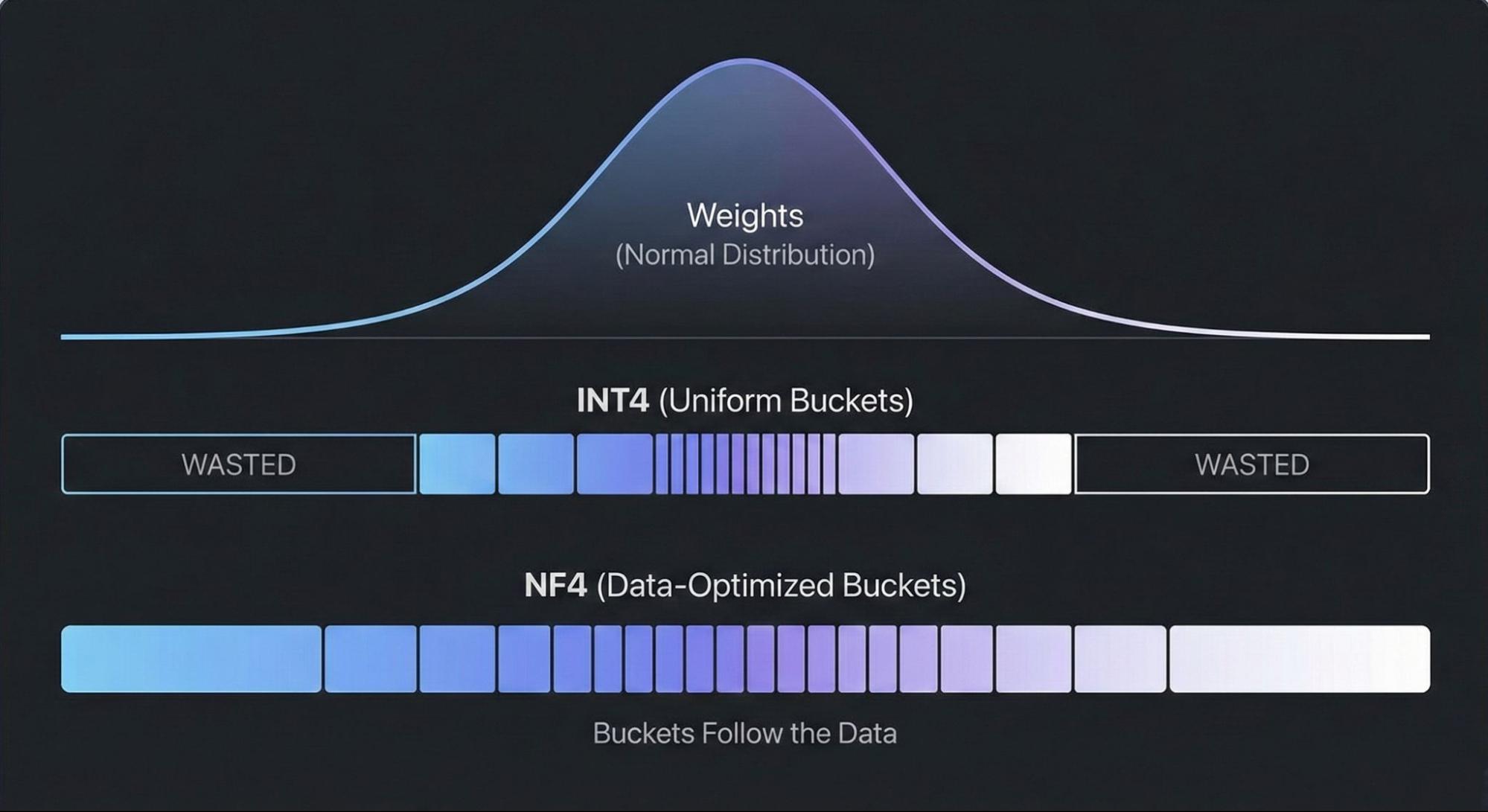

NF4 is a 4-bit quantization format from the QLoRA paper. Standard 4-bit quantization divides the number line into equal parts, but this approach wastes precision. Neural network weights usually follow a bell curve or normal distribution. NF4 improves this by using quantile quantization, which places the buckets to capture an equal share of the probability mass.

The tradeoff: NF4 dequantization is computationally heavier than standard formats, making it a good optimization target.

The puzzle rules:

- Convert NF4 weights to FP16/BF16 in a single kernel

- No large intermediate buffers

- No

torch.compile - Must run on a Tesla T4

- Target: beat Unsloth's reference time of 5.33 seconds by at least 1.15×

My Starting Point

I'm not a CUDA expert. I don't dream in PTX. But I can code in Python and TypeScript, and I'm comfortable working through problems systematically.

My workflow:

- My role: research, logic, constraints, system design

- AI tools: ChatGPT Pro + a custom Modular docs agent

- Testing: native Mojo benchmark harness (three model configs, mixed precision, 1,000 launches per matrix, strict sync for timing)

First result: 25 seconds. Five times slower than baseline.

The Optimization Path

Iteration 1: Two Kernel Designs

Within a few hours of brainstorming with AI, I had two approaches running around 8 seconds. Progress, but not enough.

Breakthrough: Packed Stores

The T4's bottleneck is memory bandwidth. Writing a single 16-bit float is inefficient; it's like sending a half-empty delivery truck. I modified both kernels to calculate two weights, pack them into a 32-bit integer, and write once.

Result: 4.25s and 4.51s. I'd passed the original 5.33s target.

Plot Twist: The Baseline Moved

When I verified against the current Unsloth implementation, it had improved to 3.70s. Ten months of optimization since the puzzle was published. Back to work.

The L4 Mystery

I ran the same kernels on an L4 GPU to understand cross-hardware behavior. The results were counterintuitive:

| Kernel | T4 | L4 |

|---|---|---|

| Unsloth Reference | 3.70s | 3.02s |

| Mojo (2D Tiled) | 4.25s | 2.59s |

| Mojo (Warp-Per-Block) | 4.51s | 2.45s |

My "slower" kernel won on L4. Why?

L2 cache. The T4 has 4 MB, which is unforgiving if your memory patterns aren't aligned. The L4 has 48 MB, which absorbed my simpler kernel's inefficiencies and let raw compute shine.

Final Push: Occupancy Tuning

Each SM can hold 64 warps. A 1024-thread block consumes 32 slots at once. With high register pressure, you fit one block per SM, leaving you with 32 warps. When those warps stall on memory, nothing else runs.

I restructured to 512-thread blocks (16 warp slots each), allowing 3-4 blocks per SM. More resident warps = more work available when others stall.

Final T4 result: 3.46 seconds.

Final Results

| GPU | Unsloth (CUDA) | GB/s | Mojo | GB/s | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T4 | 3.70s | 162.6 | 3.46s | 173.7 | 1.07× |

| L4 | 3.00s | 200.3 | 2.40s | 250.2 | 1.25× |

| A100-40GB | 1.21s | 498.2 | 0.66s | 916.2 | 1.84× |

| H100-PCIe | 0.62s | 973.9 | 0.41s | 1474.1 | 1.51× |

Layout Constants

# constants (bnb NF4)

comptime NF4_WEIGHTS_PER_BLOCK = 64 # 64 weights per NF4 block

comptime NF4_BYTES_PER_BLOCK = 32 # 64 / 2 two 4bit weights per byte

comptime NF4_BLOCK_SHIFT = 5 # log2(32) block_id = global_byte >> 5

comptime STATE2_BLOCKS = 256 # 256 NF4 blocks per state2 group

comptime STATE2_SHIFT = 8 # log2(256) group_id = block_id >> 8

comptime CODE2_SIZE = 256 # state2.code lookup table size

# block config

comptime TILE_BYTES_X = 256 # bytes processed per row tile (x)

comptime TILE_ROWS = 4 # rows processed per block (y)

comptime THREADS_X = 128 # threads along (x)

comptime THREADS_Y = 4 # threads along (y)

# Each thread handles 1 byte at `byte = block_y * TILE_BYTES_X + tx`

# plus an unrolled second byte at `byte + THREADS_X` -> 2 bytes / thread.

# So per row:

# 128 threads * 2 bytes/thread = 256 bytesThe Final Kernel

Three optimizations:

- 512-thread blocks for better occupancy

- Packed 32-bit stores to reduce memory transactions

- Manual unrolling to process two bytes per thread

fn nf4_dequant_bnb_unroll2_packed_u32_bf16(

packed_ptr: UnsafePointer[U8, MutAnyOrigin],

absmax_q_ptr: UnsafePointer[U8, MutAnyOrigin],

code2_ptr: UnsafePointer[F32, MutAnyOrigin],

absmax2_ptr: UnsafePointer[F32, MutAnyOrigin],

offset: F32,

out_ptr: UnsafePointer[U32, MutAnyOrigin],

n_rows: Int,

n_bytes_per_row: Int,

):

"""Dequantizes NF4 packed weights to packed u32 (containing two bf16 values) on GPU with unrolling.

This kernel processes NF4 quantized weights, dequantizes them using the provided quantization states

Stores the results as packed u32 values (each holding two bf16 floats).

Uses shared memory for the NF4 table and processes tiles of data with unrolling for efficiency.

Parameters:

packed_ptr: Pointer to packed NF4 weights (uint8)

absmax_q_ptr: Pointer to quantized absmax values (uint8)

code2_ptr: Pointer to state2 code table (float32)

absmax2_ptr: Pointer to state2 absmax values (float32)

offset: Quantization offset (float32)

out_ptr: Pointer to output packed u32 (each u32 holds two bf16)

n_rows: Number of rows in the weight matrix.

n_bytes_per_row: Number of packed bytes per row.

Note: Uses unrolling to process two bytes per thread for better performance.

"""

var sh_nf4 = stack_allocation[16, F32, address_space = AddressSpace.SHARED]()

var tx = Int(thread_idx.x)

var ty = Int(thread_idx.y)

if ty == 0 and tx < 16:

sh_nf4[tx] = NF4_TABLE[tx]

barrier()

var row = Int(block_idx.x) * TILE_ROWS + ty

var byte = Int(block_idx.y) * TILE_BYTES_X + tx

if row >= n_rows or byte >= n_bytes_per_row:

return

var row_base = row * n_bytes_per_row

var gbyte0 = row_base + byte

var p0_u8: U8 = packed_ptr[gbyte0]

var p0: Int = Int(p0_u8)

var idx0_first: Int = (p0 >> 4) & 0x0F

var idx0_second: Int = p0 & 0x0F

var w0n: F32 = sh_nf4[idx0_first]

var w1n: F32 = sh_nf4[idx0_second]

var block0: Int = gbyte0 >> NF4_BLOCK_SHIFT

var q0: U8 = absmax_q_ptr[block0]

var code0: F32 = code2_ptr[Int(q0)]

var absmax20: F32 = absmax2_ptr[block0 >> STATE2_SHIFT]

var scale0: F32 = fma(code0, absmax20, offset)

var w0: F32 = w0n * scale0

var w1: F32 = w1n * scale0

var b0: BF16 = BF16(w0)

var b1: BF16 = BF16(w1)

out_ptr[gbyte0] = pack2_bf16_to_u32(b0, b1)

var byte1 = byte + THREADS_X

if byte1 < n_bytes_per_row:

var gbyte1 = gbyte0 + THREADS_X

var p1_u8: U8 = packed_ptr[gbyte1]

var p1: Int = Int(p1_u8)

var idx1_first: Int = (p1 >> 4) & 0x0F

var idx1_second: Int = p1 & 0x0F

var w2n: F32 = sh_nf4[idx1_first]

var w3n: F32 = sh_nf4[idx1_second]

var block1: Int = block0 + 4

var q1: U8 = absmax_q_ptr[block1]

var code1: F32 = code2_ptr[Int(q1)]

var absmax21: F32 = absmax2_ptr[block1 >> STATE2_SHIFT]

var scale1: F32 = fma(code1, absmax21, offset)

var w2: F32 = w2n * scale1

var w3: F32 = w3n * scale1

var b2: BF16 = BF16(w2)

var b3: BF16 = BF16(w3)

out_ptr[gbyte1] = pack2_bf16_to_u32(b2, b3)

What I Learned

Mojo's advantage is that it stays out of your way. I tried a similar kernel in Triton recently but there was no obvious path for packed stores or manual unrolling. I spent time fighting the abstraction instead of experimenting. With Mojo, I could quickly test different layouts and juggle two kernel architectures simultaneously.

AI-assisted development works for GPU code. The combination of a custom docs agent and systematic experimentation let me move fast despite my lack of CUDA background.

Hardware differences matter more than I expected. The same kernel can win on one GPU and lose on another. Understanding why (in this case, L2 cache size) is where the real learning happens.

Try It Yourself

If you've been "GPU curious" but bounced off the tooling complexity, Mojo's GPU Puzzles are a good entry point. The fundamentals transfer, and you might find it more approachable than you expected.

Credit to the Unsloth team for the puzzle notebook; this work builds on theirs.

If you have questions, reach out on X @davidrobertson or follow my work on GitHub @drobertson-dev.