Compilers occupy a special place in computer science. They're a canonical course in computer science education — a rite of passage. Building one forces you to confront how software actually works: languages, abstractions, hardware, and the boundary between human intent and machine execution.

I’ve spent a large part of my career working on compilers and programming languages, so when Anthropic announced the Claude C Compiler (CCC), I paid close attention. My take is simple: this is real progress, a milestone for the industry. This isn’t just hype, but it also isn’t the end of times - take a deep breath everyone.

Not because AI built a C compiler — we’ve had many for decades — but because CCC reveals how far AI coding has progressed, and where software development may be heading next.

Compilers once helped humans speak to machines. Now machines are beginning to help humans build compilers.

Before diving in, here are the main take-aways:

- ✅ A milestone in systems engineering.

AI has moved beyond writing small snippets of code and is beginning to participate in engineering large systems.

- 🧠 AI is crossing from local code generation into global engineering participation.

CCC maintains architecture across subsystems, not just functions.

- 📚 CCC has an “LLVM-like” design, as expected.

Training on decades of compiler engineering produces compiler architectures shaped by that history, just like training on English literature produces Shakespearean prose.

- ⚖️ Likely a legal “clean room,” but a conceptual boundary test. Our legal apparatus frequently lags behind technology progress, this pushes major boundaries and raises interesting questions. Is proprietary software cooked?

- 🧐 Good software depends on judgment, communication, and clear abstraction.

AI systems don’t replace these human qualities, they amplify them.

- 🚀 AI coding is automation, not replacement.

Implementation becomes cheaper; design and stewardship become more important.

- 🧑💻 Manual rewrites and translation work are becoming AI-native tasks.

A large category of engineering effort is about to be automated, which is a big deal for “category creators” that are building new ecosystems (e.g. Modular).

- 📈 AI, used right, should produce better software.

When implementation becomes easier, humans can spend more energy on architecture, design, and innovation. We all want 10x better software - not just “me too but cheaper”.

- 📖 Architecture documentation becomes infrastructure

AI systems amplify well-structured knowledge — and punish undocumented systems. All software systems deserve high quality architecture documentation, allowing humans and AI to ramp up quickly.

The implications for engineering teams are real and immediate. At the end, I share how I'm translating these insights into concrete expectations for my team at Modular

What are Compilers? Why do they matter as an AI Benchmark?

To understand why the Claude C Compiler matters, we must first understand why compilers themselves are such a revealing test of intelligence — human or artificial.

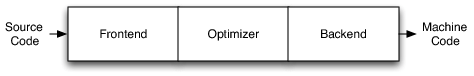

A compiler isn’t just another software project. It sits at the intersection of multiple difficult domains at once: formal language design, large-scale software architecture, deep performance constraints, and unforgiving correctness requirements.

Most applications can tolerate bugs, but compilers cannot. A single incorrect transformation can silently produce wrong programs, disrupting the productivity of countless users. Every layer must maintain strict invariants while cooperating with every other layer.

Historically, this is why compilers became a rite of passage in computer science education. They force engineers to think across abstraction layers: turning text into structure, structure into meaning, meaning into optimized machine behavior.

That process mirrors something deeper: translating human intent into precise execution, which is why compilers are a uniquely interesting benchmark for AI system integration.

Earlier generations of AI coding tools were impressive at local tasks — writing functions, generating scripts, or filling in missing pieces of code. Those tasks test pattern recognition and short-term reasoning.

The Claude C Compiler is a milestone, showing progress at a different level. It shows an AI system maintaining coherence across an entire engineering system that can coordinate multiple subsystems, preserve architectural structure, iterate toward correctness over time, and operate within a complex feedback loop of tests and failures. AI is beginning to move from code completion toward engineering participation.

However, the deeper reason compilers align unusually well with modern AI systems is that compiler engineers build architectures that are highly legible and structured. Compilers have layered abstractions, consistent naming conventions, composable passes, and deterministic feedback (“it works” or “it doesn’t” - there is a clear success criteria). These properties make compilers unusually learnable — not just for humans, but for machine learning systems trained on large amounts of source code.

Seen this way, CCC is validation of decades of software engineering practice. The abstractions developed by compiler engineers turned out to be structured enough that machines can now reason within them. That is a remarkable milestone. But it also hints at an important limitation — and understanding that limitation is where things get interesting.

Looking Inside the Claude C Compiler

One of the most interesting aspects of the Claude C Compiler is that Anthropic released the full source history. Unlike many AI demonstrations, this isn’t just a polished result or benchmark score — it’s an engineering artifact that anyone can inspect. The entire repository, including commit history, design documents, and future plans, is available. That means we can actually study how the system approached building a compiler. I spent some time doing exactly that.

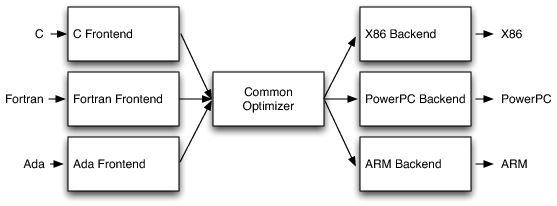

The first major commit effectively “one-shots” the basic architecture of the system. From the start, CCC follows a classic compiler structure. Major subsystems all have pretty amazing design docs too, including:

- a frontend handling preprocessing, parsing, and semantic analysis (common to all compilers),

- an intermediate representation and optimizations that are directly inspired by LLVM,

- and a backend responsible for code generation, with 4 architectures (x86-32, x86-64, RISC-V, and AArch64).

The design choices throughout the repository consistently reflect well-established compiler practice - things taught in a university class and widely used by existing compilers like LLVM and GCC. The intermediate representation includes concepts that will look immediately familiar to LLVM developers, including instructions like GetElementPtr, basic block “terminators” and Mem2Reg. It appears to have strong knowledge of widely-used compiler design techniques.

LLVM and GCC code are clearly part of the training set - Claude effectively translated large swaths of them into Rust for CCC. The design docs show detailed knowledge of both systems, as well as considered takes on its implementation approach. Some have criticized CCC for learning from this prior art, but I find that ridiculous - I certainly learned from GCC when building Clang!

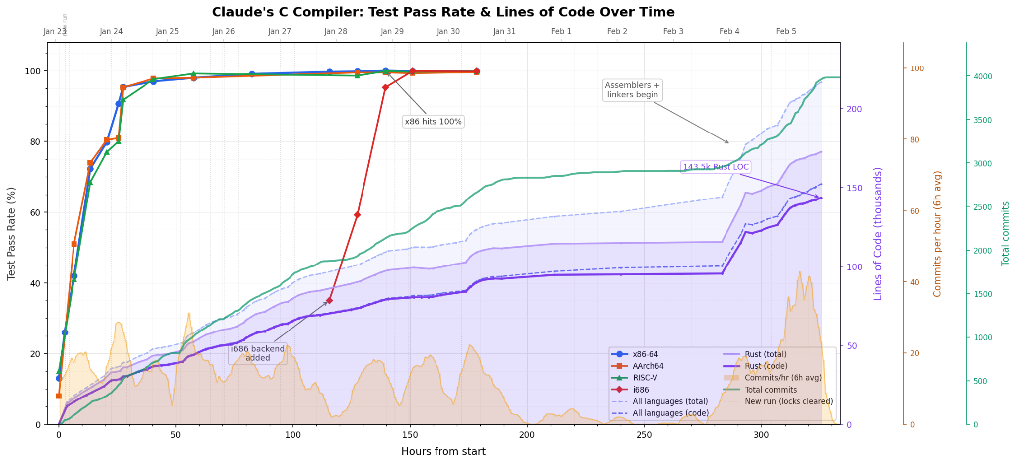

Pushpendre Rastogi wrote a great blog post about CCC and agent scaling laws, showing how iterative agent workflows gradually expanded implementation and test coverage:

Taken together, CCC looks less like an experimental research compiler and more like a competent textbook implementation — the sort of system a strong undergraduate team might build early in a project before years of refinement. That alone is remarkable.

What did the Claude C Compiler get wrong?

The most revealing parts of CCC are its mistakes. Several design choices suggest optimization toward passing tests rather than building general abstractions like a human would. A few examples:

- The code generator is “toy” and the optimizer reparses assembly text instead of using an IR, and the code generators are poorly factored.

- The parser appears to have poor error recovery / usability and have some incorrect corner cases.

- It appears that CCC doesn’t parse system headers (which are much more gnarly to deal with than application code) so it hard codes in things it needs for its tests.

This last issue is the big problem that indicates CCC won’t be able to generalize well beyond its test-suite, which appears to be confirmed by its bug tracker. These flaws are informative rather than surprising: they suggest that current AI systems excel at assembling known techniques and optimizing toward measurable success criteria, while struggling with the open-ended generalization required for production-quality systems.

And that observation leads directly to the deeper question: what does this tell us about AI coding itself?

What the Claude C Compiler Reveals About AI Coding

The most interesting lesson from the Claude C Compiler is not that AI can build a compiler. It’s how it built one. CCC didn’t invent a new architecture or explore an unfamiliar design space. Instead, it reproduced something strikingly close to the accumulated consensus of decades of compiler engineering: structurally correct, familiar, and grounded in well-understood techniques.

Modern LLMs are extraordinarily powerful distribution followers. They learn patterns across vast bodies of existing work and generate solutions near the center of that collective experience. When trained on decades of compilers shaped by GCC, LLVM, and academic literature, it is entirely natural that the result reflects that lineage. This phenomenon closely aligns with Richard Sutton’s Bitter Lesson, where scalable methods rediscover broadly successful structures.

An analogy helps. Training on English literature allows a model to produce Shakespearean prose: not because literature stopped evolving in the 1600s, but because Shakespeare occupies a dense region of the training distribution. Models learn what has been widely written and reinforced. The same dynamic appears here in compiler design (of all things, rawr! 🐉).

CCC shows that AI systems can internalize the textbook knowledge of a field and apply it coherently at scale. AI can now reliably operate within established engineering practice. This is a genuine milestone that removes much of the drudgery of repetition and allows engineers to start closer to the state of the art. But it also highlights an important limitation of this work:

Implementing known abstractions is not the same as inventing new ones. I see nothing novel in this implementation.

Historically, progress in compilers did not come from assembling standard components quickly. It came from conceptual leaps, e.g. new intermediate representations, new optimization models, new ways of structuring programs and hardware interaction. It came from getting groups of people to work together, which required inspiring and motivating engineers in new ways.

Current AI coding systems excel when success criteria are clear and verifiable: compile the program, pass the tests, improve performance. In these environments, iterative refinement works extremely well: red/green TDD works! Innovation is different. When inventing a new abstraction, success is not yet measurable. There is no test suite for an idea that does not exist, and good design is hard to quantify.

AI coding is therefore best understood as another step forward in automation. It dramatically lowers the cost of implementation, translation, and refinement. As those costs fall, the scarce resource shifts upward: deciding what systems should exist and how software should evolve.

As writing code is becoming easier, designing software becomes more important than ever. As custom software becomes cheaper to create, the real challenge becomes choosing the right problems and managing the resulting complexity. I also see big open questions about who is going to maintain all this software.

IP Law and Proprietary Software Moats

The Claude C Compiler also raises important yet uncomfortable questions about intellectual property. If AI systems trained on decades of publicly available code can reproduce familiar structures, patterns, and even specific implementations, where exactly is the boundary between learning and copying? Some observers have pointed out cases where CCC appears to regenerate artifacts strongly resembling existing implementations, including standard headers and utility code, despite claims of “clean room” development. These examples highlight how current legal frameworks struggle to describe systems that learn statistically from vast prior work rather than explicitly referencing source material.

At the same time, this situation is not new. Humans learn by studying existing systems, internalizing patterns, and reapplying ideas in new contexts. The difference is scale and automation. AI compresses decades of engineering knowledge into a generative model capable of reproducing solutions instantly. That challenges traditional assumptions about ownership when the underlying ideas are widely shared but specific expressions may still carry licenses.

We are facing a new era of automated reimplementation of proprietary software, but this doesn’t mean the paradigm is suddenly obsolete. AI lowers the cost of reproducing established designs, which will shift competitive advantage away from isolated codebases and toward execution, ecosystems, and continuous innovation. This will force legal and institutional norms to evolve, similar to when Linux and open source software first gained wide-spread adoption. Just as with those transitions, I am betting that we will see ecosystem gravity from human collaboration replace legacy ecosystems that cannot keep pace with rapidly changing times.

Automation, Innovation, and the Future of Software

If AI coding primarily automates implementation, what happens next?

History gives us a clear pattern: when the cost of building something drops dramatically, we don’t simply build the same things more cheaply. We build entirely new things.

Compilers themselves are a perfect example. Early programmers wrote assembly by hand, but once compilers became reliable, developers became vastly more ambitious and entire industries emerged because abstraction made complexity manageable. As writing code becomes easier, the likely outcome is not fewer programmers but more software. We will get more experimentation, more specialized tools, and solutions to problems that previously weren’t worth automating.

What changes is the economics of engineering work and particularly the large-scale elimination of mechanical tasks like rewrites, migrations, and boilerplate implementation. These activities are necessary but rarely innovative, and AI systems are unusually good at exactly this kind of work. Engineers move from typing implementations toward directing systems: specifying intent, validating outcomes, and shaping architecture.

As implementation becomes cheaper, the role of engineers shifts upward. The scarce skills become choosing the right abstractions, defining meaningful problems, and designing systems that humans and AI can evolve together. This will increasingly blur the boundary between software engineering and product thinking. The limiting factor is no longer whether software can be built, but deciding what should be built and how to manage the complexity that follows. AI amplifies both good and bad structure, so we can expect to see poorly managed code scale into incomprehensible nightmares.

That raises the next question: if programming is changing this fundamentally, what happens to software engineers themselves?

The Evolving Role of Software Engineers

Every major shift in software development has changed what it means to be a programmer. Early engineers managed hardware directly; later generations learned to trust compilers and higher-level languages. Each transition removed manual work while raising expectations for what engineers could accomplish — and AI coding represents the next step in that progression.

As implementation grows increasingly automated, the core skill of software engineering shifts away from writing code line-by-line and toward shaping systems — deciding what should exist, how components fit together, and how complexity remains understandable over time. Good software depends on judgment, communication, and clear abstraction. AI systems don’t replace these human qualities — they amplify them.

The most effective engineers will not compete with AI at producing code, but will learn to collaborate with it: using AI to explore ideas faster, iterate more broadly, and focus human effort on direction and design. These tools are rapidly becoming part of the normal software development stack, much like compilers, version control, or continuous integration before them. Learning to work effectively with AI is quickly becoming a core professional skill — ignoring it today would be like refusing to adopt source control twenty years ago.

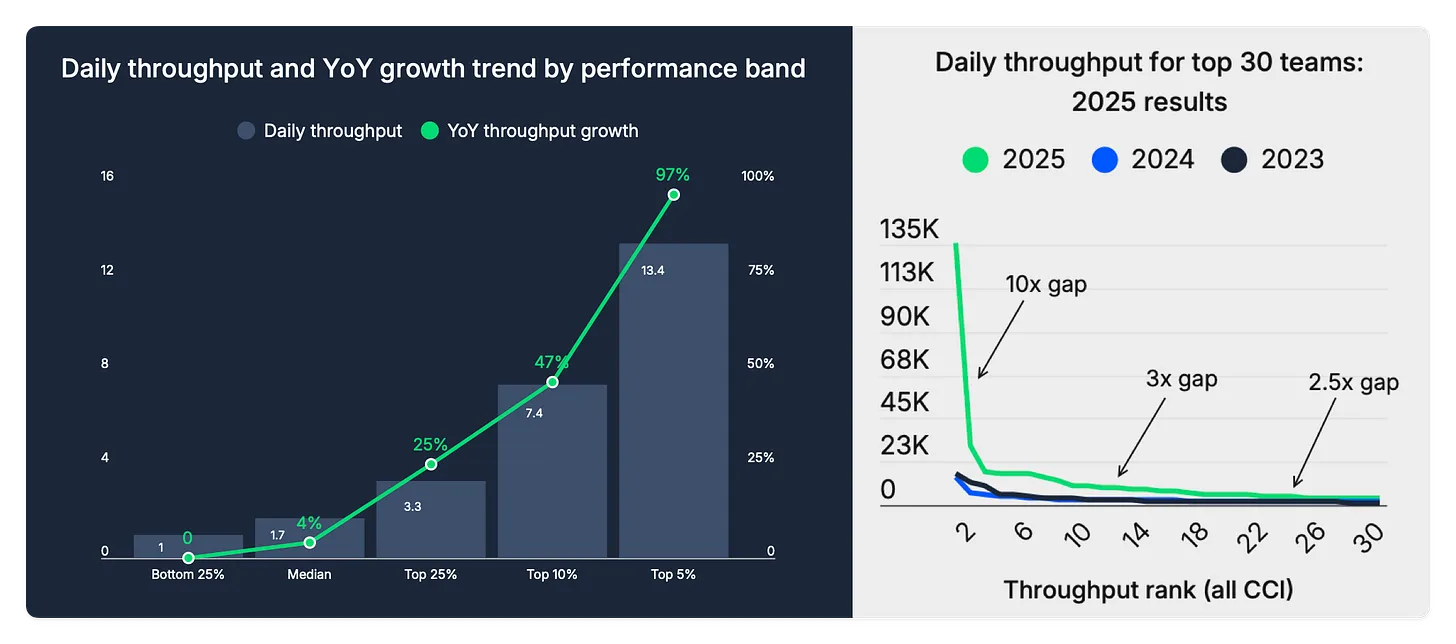

The gap between teams successfully embracing AI tooling and those that aren't is already measurable — and widening fast. According to CircleCI's 2026 State of Software Delivery Report, the top 5% of engineering teams nearly doubled their output year-over-year, while the bottom half stagnated. The most productive team in 2025 delivered roughly 10x the throughput of 2024's leader. This isn't a future risk — it's a present reality.

Which raises a practical question: how should teams actually adapt?

Here's how I'm translating this shift into concrete expectations for Modular.

How I Expect Modular to Adapt to AI tools

Developments like the Claude C Compiler have changed how I think about engineering work and what I now ask from my team. Fully benefiting from AI tools requires a deliberate leap: habits formed over decades don’t change automatically, and organizations rarely transform just because better tools exist.

At the same time, we need to be pragmatic. AI systems are powerful but far from perfect. Progress comes from collaboration with AI, not abdication to it. The goal is not to remove humans from the loop, but to move humans into higher-leverage positions inside it.

That leads to three concrete expectations:

1️⃣ Adopt AI Aggressively — but Stay Accountable

Every employee — engineering, G&A, and GTM alike — is expected to actively adopt AI tools to accelerate productivity and decision-making. The world is moving quickly, and we must lean into change.

But responsibility does not transfer to the tool. For example, engineers building large-scale production software remain accountable for correctness, design quality, and long-term maintainability. AI expands our capabilities, but it does not outsource judgment. Work produced with AI should be understood, validated, and owned just as deeply as work written by hand. Reputation is still built on outcomes, not prompts.

2️⃣ Move Human Effort Up the Stack

A large fraction of historical engineering effort has gone into mechanical work: rewriting code, adapting interfaces, migrating systems, and reproducing existing patterns in new environments. AI is rapidly becoming better at these tasks than humans. We should not compete with automation at mechanical work. Instead, engineers should clarify intent with rigor, validate outcomes with tests, and improve their design.

Human effort should concentrate where creativity and judgment matter most — and all engineers now have management responsibilities. As migration and implementation accelerate, architectural evolution is no longer limited by how fast humans can rewrite software, but by how clearly we can define where systems should go next.

3️⃣ Invest in Structure and Community

AI amplifies structure.

Well-documented systems become dramatically easier to extend and evolve; poorly structured systems scale into confusion faster than ever. Documentation, clear interfaces, and explicit design intent are no longer optional overhead — they are operational leverage.

As implementation costs approach zero, the scarce resource shifts from writing code to aligning people. The greatest opportunity lies in building communities of like-minded people that collaborate toward shared goals — ecosystems where developers can move forward together instead of repeatedly rebuilding the past.

For my team, that means focusing on tools and platforms that help other developers succeed: systems that move existing code forward, unlock modern compute, and enable collaboration between humans and AI. This aligns directly with Modular’s mission to Democratize AI Compute and expand what programmers everywhere can create.

Closing Thoughts

The Claude C Compiler doesn’t mark the end of software or compiler engineering — it marks the beginning of a new era of creation. As software implementation becomes easier, the opportunity to innovate grows larger.

Lower barriers to implementation do not reduce the importance of engineers; they elevate the importance of vision, judgment, and taste. When creation becomes easier, deciding what is worth creating becomes the harder problem. AI accelerates execution, but meaning, direction, and responsibility remain fundamentally human.

Writing code has never been the goal. Building meaningful software is. The future belongs to teams willing to embrace new tools, challenge assumptions, and design systems that help people create together.

That is the future that has driven Modular’s mission from the start — and the one I believe this new era of AI makes possible.

-Chris Lattner

______

Want to build the AI future with us? Modular is hiring.